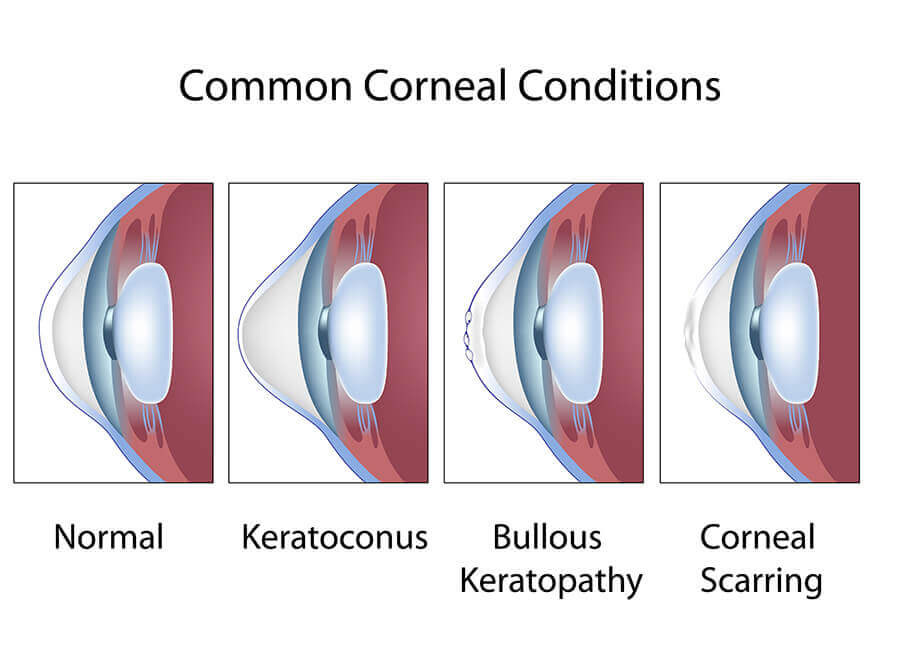

Keratoconus

Keratoconus is a degeneration of the structure of the cornea. The cornea is the clear tissue covering the front of the eye. The normal corneal surface is smooth and aspheric (round in the center, flattening toward its outer edges). In patients with keratoconus, not only is the cornea cone-shaped but the surface of the cornea is also irregular, resulting in distorted vision.

The cause of keratoconus is unknown but the tendency to develop this condition is probably present from birth. It is possible that the condition involves a defect in collagen, the tissue that makes up most of the cornea. Some researchers also believe that eye rubbing may play a role, although evidence supporting this theory is largely anecdotal.

Symptoms and Treatment

Most patients are unaware that they have keratoconus as the earliest symptoms are a subtle blurring of vision and slow changes in their vision that initially that can be corrected with glasses. Most people who develop this condition start out nearsighted. The nearsightedness tends to become worse over time and while such patients’ vision can generally be corrected to 20/20 with rigid, gas-permeable contact lenses, severe cases of keratoconus may require corneal transplantation. Some newer treatments, such as corneal collagen crosslinking, may delay or even prevent corneal transplantation.

Corneal Collagen Cross-Linking for Treatment of Keratoconus

NY Vision Group has been investigating treatments for keratoconus and is now offering Corneal Collagen Crosslinking for use in the treatment of keratoconus and corneal weakness (ectasia). Corneal collagen crosslinking (CXL) was developed in 1998 by Theo Seiler, MD, in Zurich, and has been shown in numerous clinical trials to strengthen the cornea through the application of riboflavin, a form of vitamin-B2, followed by treatment with ultraviolet A (UV-A) light. Dr. Koster recently attended the 16th annual international Crosslinking Conference (CXL) in Zurich, Switzerland. This is the premier conference for crosslinking and he felt it important to attend to better understand the nuances of decision-making and treatment related to crosslinking. Every major researcher and clinician in the field presented on varied issues of this field. To date, the European experience has been significantly more advanced than in the US, since the FDA only recently approved this therapy. One of the biggest takeaways from the conference was the need to identify patients with keratoconus as early as possible.

A joint panel of the FDA’s Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee and Ophthalmic Devices Panel voted to recommend approval of Avedro’s technology (Waltham, Mass.), a drug-device combination of riboflavin ophthalmic solution and UV-A light for crosslinking for both progressive keratoconus and corneal ectasia following refractive surgery. Crosslinking with riboflavin and UV-A light has proven to be a first-line treatment for people with eye conditions such as keratoconus and corneal weakness (ectasia) after LASIK.

There are two basic types of corneal cross-linking:

Epithelium off (also known as the Dresdon Protocol), which means the thin layer covering the eye’s surface is removed, allowing for faster penetration with liquid riboflavin. This approach involves soaking the cornea with Riboflavin for 30 minutes followed by crosslinking with Ultraviolet light for 30 minutes. Newer protocols, not approved in the US, call for accelerated faster treatments with good results.

Transepithelial corneal crosslinking (epithelium on) is where the corneal epithelial surface is left intact, which requires a longer riboflavin loading time. There are theoretical advantages of quicker recovery and no complications with surface healing.

For the Dresdon Protocol (epithelium off), success rates for stability are high, with over 90% of treated patients being stabilized with one treatment for at least 5 years.

The best candidates for corneal cross-linking are:

- Patients with progressive keratoconus

- Patients considering vision correction procedures such as LASIK might eventually be pre-treated with corneal crosslinking to strengthen the eye’s surface beforehand

- MOST IMPORTANT: Treatment of Keratoconic patients before the disease has significantly affected their vision.

Our practice offers the procedure (the Dresdon Protocol) to appropriate patients, in office, as a means to intervene early and arrest progression with possible need for more risky intervention, such as corneal transplant surgery. We hope to be at the forefront of reasonable therapies, as borne out by rigorous scientific evaluation. This includes further collaboration with Swiss companies and European colleagues as necessary.

Pterygium

A pterygium is a fleshy, exaggerated growth of the conjunctiva (the clear, thin tissue) that lays over the white part of the eye. The growth extends on top of the cornea and has the appearance of growing over the iris. One or both eyes may be involved. The cause is not known, but it is more common in people with excess outdoor exposure to sunlight and wind, such as those who work outdoors, so it is thought that ultraviolet light exposure may have a role in causing this condition chance of this condition.

A pterygium is a fleshy, exaggerated growth of the conjunctiva (the clear, thin tissue) that lays over the white part of the eye. The growth extends on top of the cornea and has the appearance of growing over the iris. One or both eyes may be involved. The cause is not known, but it is more common in people with excess outdoor exposure to sunlight and wind, such as those who work outdoors, so it is thought that ultraviolet light exposure may have a role in causing this condition chance of this condition.

Symptoms and Treatment

The main symptom of a pterygium is a painless area of raised white tissue, with blood vessels on the inner or outer edge of the cornea. Sometimes a pterygium becomes red and inflamed and causes burning, irritation, or a foreign body sensation. A routine eye examination can confirm the diagnosis. Special tests are usually not needed.

No treatment is necessary unless the pterygium begins to distort vision, causes symptoms that are hard to control or is significant cosmetically. When medical therapy is inadequate the pterygium, may be surgically removed.

Surgical removal of a pterygium, even if it affects the cornea, is highly successful and uncomplicated. The procedure is performed under local anesthesia. The main concern in performing the procedure is to minimize the chance of recurrence. Often the visually apparent pterygium is like the tip of an iceberg, with extension beneath the conjunctiva. Thus successful excision requires meticulous pursuit of other diseased conjunctiva. Techniques now include the use of topical antimetabolites (Metomycin C), amniotic membranes and conjunctual autografts to improve post-operate aesthetics and minimize the possibility of recurrence. Additionally, instead of using dissolving sutures which may increase recurrence rates, grafts are secured using medically approved glue. This results in superior patient comfort and appearance post-operatively. Our experienced surgeons routinely perform such procedures at Dr. Koster’s surgery center in mid-town Manhattan.

A pterygium can return after it is removed. Patients who have had them removed should wear protective glasses and a hat with a brim to prevent the condition from returning. Furthermore, people with pterygium should be seen by an ophthalmologist each year so that the condition can be treated before it affects vision.